How it all began

From college graduation in 1969, until 1978, I was employed by several different firms as a programmer, systems analyst, and general “computer guy”. This was at a time when most women with children were still stay-at-home moms. They hung out together, watched each other’s kids, and built strong friendships. I was bored out of my mind in a stifling job, envying the crowd of experimenters building personal computers they could use at home. With the tacit approval of my wife Diane, I quit my job and joined them.

Many of the fruit orchards in California were slowly becoming Silicon Valley. Freedom from employment allowed me to be creative, and I made a number of software products that were sold through startups catering to the growing home computer market. I did not get stock options, did not become a millionaire, or have any of the perks that programmers on the west coast would later fall into. We were not rich, but we lived comfortably. Diane had an informal business sewing for people, using skills she had accumulated since the age of 6.

Once all three of our sons were in school, Diane was bored and ready to embark on a career of her own. She got a job at a local chain store selling sewing machines. Unlike most of the staff in the store, she could teach people how to use the machines they bought. With some persuasion, she got the store manager to let her run classes. Being unencumbered by a job, I could be home when the boys came home from school, and manage some of the household chores.

Diane met a saleswoman working for the same chain store in a different location, and they became friends. On one of their days off they thought it might be worthwhile to go to one of the local independent sewing machine stores to see how “professionals” sold them. They visited one of the oldest and largest stores, which sold the same brands of machines as their employer.

At the time just about every single independent sewing machine dealer was male. Many of them also sold vacuum cleaners, and the store name would end in “Sew and Vac”. This was a holdover from days when vacuums used the same motors as sewing machines and it was convenient to sell both. Even though there is now no overlap between sewing machines and vacuums, the name has stuck.

The first thing the women noticed on entering the store was the complete lack of pricing on any sewing machine. Diane pointed to one top of line model and asked how much it would cost. The answer would change our lives. The owner told her “Well honey, you come back with your husband and then we’ll talk price.”

That night, when she related this to me, her red hair threatened to ignite from her fury. She wanted to show them that she could do a better job. I suggested that she consider opening her own store. We put some numbers into a spreadsheet, and it looked like it might work. As confirmation I consulted with a client who had started multiple businesses and he agreed it was feasible.

Class is in session

Diane was reluctant to chuck a job that she liked, and risk failure in opening a store. After she had spent a couple weeks on the fence, I wrote out a letter of resignation for her. She carried it in her purse until one of her paychecks again failed to include her commission. Then she submitted it. Game on!

Diane’s friend from another store also quit her job. The two of them traveled to a convention of sewing machine dealers to see about getting dealerships. They got confirmation that the industry was quite misogynistic, but for manufacturers the prospect of selling dealerships overcame patronizing skepticism. The brand both women had been selling refused them, simply because they would be competing with the very stores that had previously employed them. However they found another brand they liked even better. A dealership was possible with an opening order of just $5,000.

At this point we didn’t have more than a few hundred dollars. There was no business plan, as we didn’t know how to make one. When you decide to open a business, you’ll have many people tell you that 90% of businesses fail in the first year. That’s probably true, and most of those that failed probably had a business plan and funding. All we had was faith that we could do it.

The first lesson happened at the bank. I made an appointment to get a loan. The loan officer asked to see our business plan, so I gave him our spreadsheet. He looked it over and asked what we had for collateral. First lesson! When it comes to borrowing money from a bank, know that you will only get it if you can prove that you do not need it. Our collateral was a house with a mortgage and a car with payments. Our checking account at that bank did not help, as it rarely got to a 4-digit balance. Request denied.

Another source of funding is the friends and family approach. None of our friends had any more money than we did, and our families were middle class, without any surplus cash floating around. It wasn’t looking good, but then an offer appeared in the mail from the financial company that was managing our IRA accounts. They offered $4,700 on a signature loan, no collateral required. We had good credit, so we signed and got a book of checks. Inventory ordered, first problem solved.

While there are some retail businesses that can be run from home, it is not legal in most cities. Neighbors get testy about cars being parked all over their street, and deliveries can be problematic. We needed a storefront. Knowing nothing about commercial real estate, we contacted a realtor.

Luck was with us, as the woman we chose found us a location that was walking distance from our house. It was small, but big enough for our purpose. It had been a real estate office, partitioned into 3 different spaces. A little weird, but we could use it without the expense of remodeling. The only sticking point was that we would need a sign. Our realtor suggested asking the landlord to make the sign, and they agreed. We stayed in this location for two years, and were the longest tenant in that space.

The next 22 years would see us moving 4 times. Each time involved signing a commercial lease. These are long legal documents that you absolutely should not sign without having a lawyer review. While we did incorporate, you should not assume that doing so will protect you from lawsuits. Virtually every lease has a requirement for a personal guarantee, meaning if you break the lease you will be responsible for all expenses yourself.

Also do not assume that you need to accept the lease as written. Part of the negotiation process is to disagree with some items, such as being responsible for the roof. Clauses like that are built in to benefit the landlord. You can cross them out and initial before signing, providing it is agreed by the landlord.

Another gotcha to avoid is percentage rent. This is a given when setting up shop in a mall, but can usually be negotiated out for strip centers and freestanding buildings. Percentage rent means paying the landlord a percentage of your gross sales. If your business is very successful that can be costly, so avoid it if at all possible.

Then there’s the rent. If you are just starting out you want it as low as possible. Most landlords understand this, and will offer a stair step lease. These start out low(ish) and increase year by year. In our last location we paid $5,500 per month in year 1, stepping up to $7,000 in year 5. This was on a space of 2,400 square feet.

Rent isn’t the only big expense. There’s also finish-out, which is the construction necessary to convert the space for your purpose. This can be very expensive. In our 4th location the space we rented was just an outline on a concrete slab in a strip center. We had to provide everything, starting with the walls. Again we had no idea how to get started. The first task was to get a drawing for the construction. We called a local firm for a quote.

A day or so later a representative came in, suit and tie, ultra professional. He was sure he could do the job for us. The drawing would cost $10,000, and then they would be able to estimate the construction cost. It took a while to get our breath back after he left.

Next we called the son of a customer. He had done some work on our home, so we knew him to be good. Unfortunately he had moved to a city 300 miles away. But he referred us to a former partner who could do the job. We called him. The next day a guy walks in wearing sweats, speckled with bits of plaster and paint. He says he will do the job for a percentage of the overall material and labor cost. And he has a retired NASA engineer who will do the drawing for $400. Finding Butch was key.

The Hardest Lesson

Commercial construction is expensive. Really expensive. Our two moves were to locations that were already finished to the point that we didn’t have to do much more than paint and add fixtures. When we committed to an unfinished space with nothing more than a roof and a floor, there was much to do, all of it costly.

At the time I had a friend in the residential heating and air conditioning business. I’d helped him a fair bit with his computer. He offered to get us the air conditioners at his cost, and install them without charging for labor. I agreed to that, against Diane’s reluctance. (Side note to husbands - pay attention to your wife’s intuition. If she says something doesn’t feel right, trust her!)

Just a few days after construction started I got a very angry call from the landlord. My friend, unfamiliar with commercial construction, had cut the holes in the roof for the A/C units outside the load-bearing zone specified on the plans. That could necessitate us replacing the roof, which would have required us to sell our house and probably bankrupt us.

Fortunately Butch saved us. His engineer friend found that the weight of the equipment we were using was low enough to allow using the misplaced holes. I was ready to cut my friend loose, but Butch had a serious talk with him and said he thought we could trust him to finish the job.

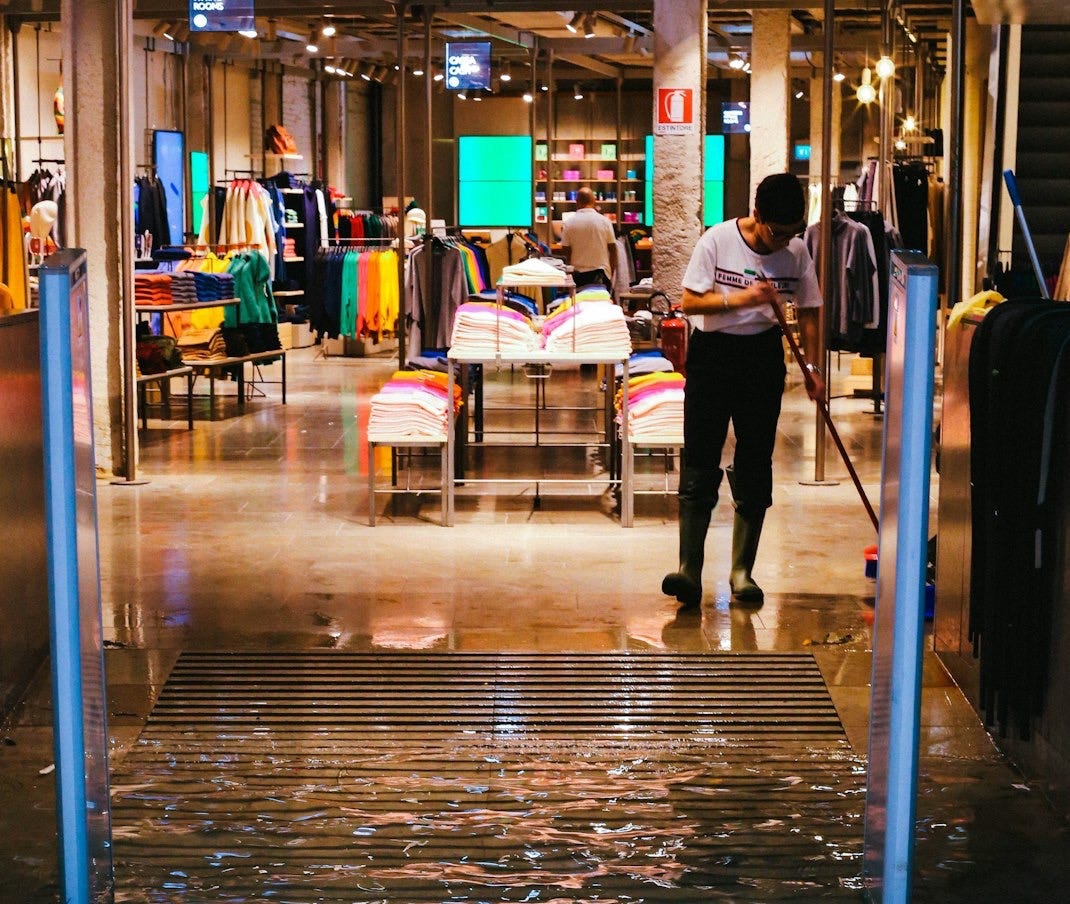

Over the next few days my friend was only working at night, since he had his own business to tend to during the day. Just as we were preparing to go to bed one night, we got a call from him. He said that one of the pipes of the sprinkler system had fallen off, and water was spraying all over. We went to the store immediately, in time to see the fire trucks leaving. They had been called automatically by the water flow triggering an alarm.

Seeing a large pile of sheet rock, that we’d already paid for, soaking up water from the flood that still remained was devastating. Worse was the fact that the intense pressure of the sprinkler system had blasted a hole through the wall and flooded the shoe store next door that was about to open for business. We had no time for tears.

I had a client that did restoration of homes after fire and water damage, but I could not reach them at 2am. Realizing that time was of the essence if we were going to avoid a lawsuit from our neighbor, I hit the Yellow Pages. (This was in the days before Internet.) Amazingly one of the numbers I called was answered by the owner. Within an hour he was there, installing industrial dehumidifiers powered by generators, as we had not yet gotten electrical service.

Once we got recovery operations started, we were able to determine what happened. The roof of this facility was very high. A scissor lift was on site, used by the sheet rock crews to put up the walls. Sprinkler pipe crossed over at the roofline, with long pipes hanging down to ceiling level. Apparently in the dark, with only one light, he brought the scissor lift up under one of the pipes, breaking it off at the roofline. The pipe was bent, which could not have happened any other way. Of course my friend denied this, claiming the pipe just “fell off”.

We were able to fix the damage done to our neighboring store, and they opened as expected. Butch got us a different air conditioning firm, and they began the work of installing the systems correctly. Most of the material we had paid for had to be thrown away, because it was not right for the job. The city required all construction firms to be insured, so I filed a claim with my friend’s insurance company for the damage.

Several weeks passed, with the insurance company completely stonewalling me. I finally hired an attorney and filed a lawsuit against my now-former friend. It took 2 years and $12,000 in legal fees to recover $5,500 from the insurance company, for damages totaling $11,800. I came away realizing that a “brother-in-law” deal in any kind of business endeavor is a huge mistake. Do not do business with friends or family!

The whole debacle set us back on our schedule, as we were trying to have the new store opened before our lease expired on the existing one. One of Diane’s friends put us on to a strategy for expediting construction. Every morning, before opening our current store, we would stop at a donut shop and buy a couple dozen doughnuts. Then we would leave them at the job site, along with a coffee pot we’d bought. Butch told us that subcontractors on other jobs would come to work on ours, just because of those perks. It was a cheap way to speed things up, and it got us moved in just in time.

Operational Lessons

Moving in to our fourth location was a turning point for us. I’d had a single client that took all of my time, but paid very well. They started having financial difficulties, and I could see that it was not going to end well. So I stopped doing my consulting work and joined Diane full time. I’d been doing the books and sewing machine repairs, but Diane taught me enough sewing to properly demonstrate a machine.

We also had to add a couple of employees. This gave us another lesson. No matter how good they are, your employees will never place nearly as much importance on your business as you do. Once or twice each year we would have to be out of the store for a few days to attend trade shows. Sales would always drop during those times. On one such occasion, I called to see how things were going. An employee had given a refund that would exceed our bank balance. I had her run a charge on my own credit card to prevent overdraft. This was against the rules of the credit card company, but I had no other options.

Because we dealt in sewing machines and supplies, almost our entire customer base was women. For the first few years of operation the demographic was mostly women aged 50 and up. They were products of an educational system that included Home Economics classes in high school. Having learned to sew, they continued to do it as a hobby, though some also made their own clothes.

In an effort to grow our business, we started giving “How to Sew” classes to younger women. That worked really well, and soon we had women of all ages coming in. During the summer we ran classes for kids. This was mostly girls, though we did get one boy.

As the repair technician, I dealt with machine problems. There was a stark difference in the way women presented problems. Those in the 50+ age range would start out by saying “I don’t know what I did, but it’s not working.” I realized that they had become conditioned over the years to accept that they were not competent to understand things of a mechanical nature. Worse, the misogynist nature of the male dealers had used this to their advantage. Every repair they accepted would begin with “What have you done?”

We won a lot of customers over the most common sewing machine problem. The needles used in household sewing machines have a flat side. When inserted in the machine, the flat needs to go to the back. Even though there are guides in place to ensure placement, on a lot of older machines it was easy to put the needle in backward. This would cause the machine to break thread and not make decent stitches.

Our competition used the backward needle problem as leverage. They would take a machine in, after advising the customer that it was seriously damaged. Then they would flip the needle, let it age a few days, and call the customer back to present a large repair bill. Since the customer did not know what was done to fix the problem, it would happen again. After enough cycles, the dealer would suggest that the machine was worn out and sell them a new one.

We could spot the problem right away. Each time we would turn the needle around, sew enough to show it was “fixed”, and instruct the customer on the proper way to insert the needle. All this was done at no charge. Needless to say, this infuriated our competition, but built a lot of customer loyalty.

Unlike our competition, we treated all of our customers the same. I remember one woman who came in and asked to see a demonstration of our top model. It was over $1,000. She was dressed in very worn clothes and looked like one who was used to being ignored. I spent more than half an hour showing her all the features, and gave her a brochure to take home. For most prospects this type of demo would end by “going for the close” and ask if she’d like to take it home. I sensed that might lead to embarrassment, as I didn’t think she could possibly afford it, so I didn’t press. We had prices on all the machines, so she knew how much it would cost. She thanked me and left.

Almost two years later this same woman came back. She said “I’d like to buy that machine.” She paid in cash, small bills that she had obviously been saving for some time. We didn’t see her a lot after that, but she did come in to show off the things she had made for her grandchildren.

The obvious lesson is that you cannot judge someone’s financial status based on how they look. We had customers that drove expensive cars, wore fine clothes, and even had high-paying jobs. Yet they would be denied when applying for credit for a $400 machine.

Our weekend clubs and classes were very popular. Many of those attending were seeking an escape from problems at home or work. Sometimes when they paid for their purchases they would pull out a three-inch stack of credit cards. When one was declined, they would shuffle through the deck, and say “Try this one.” On purchases of $100 or less by regulars, I would sometimes apply my own “secret discount” and ring up the sale. We never spoke about it, but their tears of gratitude told me it was the right thing to do.

Coda

While we had plenty of challenges getting Diane’s store off the ground, we also had a lot of fun doing it. It became like the old sitcom Cheers, where everybody knows your name. Our customers became friends, and then like part of an extended family. At times we were like bartenders, as they shared their joys and frustrations.

One common misconception that people have about family-run businesses is that the owners must be wealthy. It’s easy to jump to that conclusion when the store has a large inventory of very expensive products. After all, if you buy something for $100 and you sell it for $200, you’ve made $100, right? That’s true. But that $100 gross profit has to be applied to employee payroll, rent, and utilities. At our peak, when our annual gross sales were almost a million dollars, we took home just over $50,000.

It’s not uncommon for small businesses to fail when the owners are living out of the cash register, ie taking money from the till for personal expenses. You have to be scrupulous and relentless in keeping the books. More than once we had to use our own personal credit cards to keep going.

Many times one of our regulars would say how surprised she was that Diane and I could work together. While we had some insanely stressful times, it strengthened our bond. It felt like we were sodbusters on the prairie, pushing a plow side by side.

We won several sales incentive contests from the company whose machines we sold. Top dealers were taken on all-expense paid trips, and we were able to go to England, Scotland, Vienna, Greece, and other places we would never have been able to visit on our own.

There was a time in America when family-run businesses were the norm. They knew their customers by name, and were fixtures of the community. The end of this started with Walmart, which came through town after town, destroying the small local businesses. Following that came the “Big Box” stores doing the same thing. Capping it all is Amazon.

We probably could have kept going for another 10 years or so, but we chose to close in 2011. Retirement gave us time to pursue hobbies, improve our health through diet and exercise, and enjoy our remaining years to the fullest. We have lots of fond memories, and no regrets.

I love this article. In this day and age starting a low margin small retail business would be seen as financial ineptitude by many; but it seems like an enviable working life; challenges yes, but to have a sense of personal accomplishment and ownership is so rare when most people are cogs in a machine without any autonomy, or spend their energy buttering up their bosses or looking busy so as to not lose their jobs.

In 2019-2020 I was planning to take over an underperforming cafe with an oversized space on the Westside of Los Angeles.

I love the fact that you were able to create a “third place” and have classes and create community. I had a similar third space business and thought I could really utilize the square footage and create multiple income streams from selling books, founding memberships with perks for regulars that like to work in coffee shops, and having evening/weekend events and using some zoning tricks to get a beer and wine license for them.

Ultimately, I couldn’t quite get the spreadsheet to work, the landlord was doubling the lease, and I didn’t have quite enough cash to provide the runway to get to where I thought it would be profitable enough to cover my bills. I was lucky I guess because the pandemic hit a few months later, and a place that relied on face to face interaction would have been dead in the water.

Given the fact that socializing and third places are disappearing I’d say that a place like this would be even more in demand. Most people I know want to get off their phones and Netflix and have a place they can go and be around other people.

Hilarious. Regarding the comment on the lemonade.

Many years ago we went to a 31 flavors in Milwaukee often. We loved it. The owner was probably in her 70s and she was quite friendly. You know it's that personal attention. Well, we were there at closing time once,we saw her sampling each bucket with her finger, ewwww. Yup, very deliberate. Not even an oopsie. We didn't go there again and couldn't finish our ice cream either.